The Final Lesson

April 24, 2023

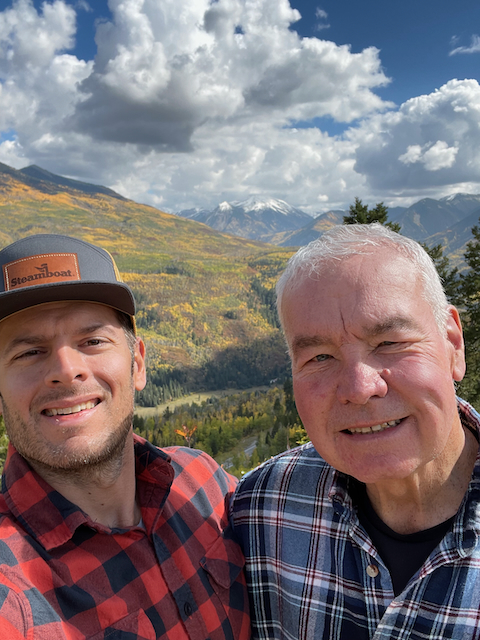

Last year I lost my father to cancer just days before his 69th birthday. He was a great father and also my best friend. I was 38 years old when he died.

In 2018 my father developed a cough that never went away. In 2019 he had over 1 liter of fluid drained from a pleural effusion and a large tumor was found in his lung. It was March, I was eating at the Chipotle in Silverthorne after snowboarding with my friend at Breck — I was having a good day — then I got the call. It was my parents, both of them, “we have some news” one of them said. I can’t remember who said it because what followed put me into a state of shock: my father was diagnosed with Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. It turns out you almost never catch lung cancer until it’s Stage IV.

Fast forward three years to January 17, 2022. Mom hears a noise coming from the bathroom. She enters to find my father naked, wedged between the toilet and the wall, and he appears to be seizing. My father’s cancer was under control, the tumor had shrunk and his brain scans were clear, but over time he had developed a loss of balance. His neurologist believed that along with the cancer he had developed an accelerated case of white matter disease — a condition that can greatly affect your balance. I was at my home in Colorado at the time, 1,800 miles away, so I couldn’t assess his condition directly. Everything I heard made me think it was an acute injury from falling; but it would turn out to be something much deeper.

A week later I enter the ICU at Hershey Medical in Pensylvania. My father’s condition is not improving and no one has an answer. The first time I see him it hits me like a baseball bat to the chest. Physically my body is moving forward towards him, but metaphysically my soul is stopped at the door. My soul knew what my brain couldn’t yet comprehend.

I put my hand on his chest, grasped his hand with my other hand, and began talking into his ear: “I’m here dad, and I’m not going anywhere.” I felt a slight grab of my finger — the last touch my father would ever give me. The doctors said he was unresponsive to most stimulus and that the anti-seizure drugs they gave him would keep him knocked out, but that he would come off those drugs tomorrow if he showed no signs of seizing. They didn’t have a solid answer for his current condition. They believed he had a pressure build up in his brain causing inflammation and general unresponsiveness. That day they performed a lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), allowing them to get a better idea of what was going on inside of his brain. His intracranial pressure was high, confirming the doctor’s symptomatic hypothesis while also explaining the migraines my father had complained about the weeks prior. But we still didn’t know why this was happening, that’s what the CSF would hopefully tell us. After the LP I spent the rest of the day by my father’s side.

The next day I was more prepared for what I was going to see. I was determined to focus all of my energy on being with my father and making sure the doctors were doing everything they could to make my him well again. My brain was still determined to fix this. Immediately upon entering the room I once again put my hand on his chest and spoke: “It’s Ryan dad. I’m here and I’m not going anywhere. You’re going to get through this.” He was still coming off the anti-seizure drugs so he couldn’t open his eyes, but I noticed that it looked like he was trying to open them. Then a single tear fell from his left eye and rolled slowly down his cheek. I began to say something else while rubbing his chest. Another tear, this time from his right eye. A doctor walked in mid sentence and I immediately stopped and turned around: “he reacted! he’s crying!” I said. The doctor came to the bedside and performed some checks. I watched every detail of every move he made, studying his face looking for the truth. The doctor could tell I was excited. He tempered me by saying the tears could have been a simple physical reaction to the air vent above the bed, causing my father’s eyes to dry out. I understood why the doctor was saying this, but I also knew he was completely fucking wrong. My dad laid under that vent for days and that was the only time I saw tears.

I went into the third day with hope. My father had begun opening his eyes the previous day, looking directly at me when I would stand by his side. He had no other movement and he couldn’t speak, though he tried a few times. I was hopeful. The doctors at Hershey Medical had been studying his condition for two days, we were about to have the CSF results, and overnight they had done an MRI of his brain. Armed with this information I figured we’d finally have some answers — and we did. They said I should call my mom and have her come to the hospital so they could discuss the results with both of us together. That should have been my sign. During this time, due to COVID-19 rules, only one person could visit for the entire day. You couldn’t have multiple people visit, even during different times. It was a terrible rule.

Later that day the oncologist enters the room and asks my mother and I to sit down. The doctor spoke with his soft Indian accent that was hard to understand at times. He danced around the issue for a bit in some attempt, I suppose, to soften the blow. But eventually the safety pin was pulled, the striker lever released, and the grenade “Leptomeningeal metastases” was thrown into the room. Everything went white. I could see the doctor still talking but nothing got through. The world started moving in slow motion until it was as if time itself had completely stopped for a moment and only a singular thought could exist: my dad was going to die. I would later learn that these words the doctor spoke were a fancy way of saying that there is no way we could have seen this coming and that it was terminal. We had days.

I sat at my father’s bedside for the next four days and watched nature take its course. I spoke to him often and let him know I loved him and that he was my best friend. I let him know that he wasn’t alone, that I was going to be there with him until the end. I watched as family and friends said their goodbyes. On the second to last day my dad’s three best friends, his childhood friends, came to visit. They did everything together while growing up until life took them on their separate ways. Now, in that hospital room, they were rejoined for one last hurrah. His friend Fab said “you’re a real meat packer Mike, you know that?” — everyone laughed. My dad reacted, moving his eyes and trying to speak. He had been off all drugs for several days so that he could die in peace. And, being the hard son of a bitch he was, he tried talking to us with that scrambled brain of his. I hope one day I’m half as strong as he was.

The last day it was mostly just me and my father — I liked that. In my life we spent a lot of time together, just the two of us. Driving, fishing, golfing, working on a house project. If it involved something outdoors or building something with our hands, we did it together. These were my favorite times with him, just enjoying each other’s company. It was fitting that our last day together was a lot like that. It felt peaceful. It felt right.

Part of that peace might have come from an epiphany I had the day before. I realized two things. First, my dad was my best friend. I spent a lot of time with him in my adulthood, and reflecting back on those times it suddenly dawned on me that I hung out with him not because he was my father, but because I enjoyed being with him.

That said, he was still my father, and even on his death bed he had one last lesson to teach me. The final lesson, my second epiphany: memento mori. We all know what it means. We all know it’s coming for us, probably sooner than we expect or want. But how many of us really sit with it? I’ve seen death before. I lost a friend in high school and another at 28, but I wasn’t ready to really see it back then. Death was something that happened to other people. But in those final days with my father I saw it. I looked it straight in the eye. I embraced it. I made peace with it. And I decided to learn from it. My father, in his own way, made the intangibles of death very tangible to me that day. He gave me the final lesson I would need to live the rest of my life.

It’s been over a year since that day. I recently turned 40; and in my mid-life crisis I’ve taken my father’s final lesson to heart. I quit my well-paying job as a software engineer. I spent most of the winter snowboarding, something I’ve wanted to do since moving to Colorado and learning to snowboard. I’m reading books on business, mythology, as well as great works of fiction. Last week I became a CrossFit Level 1 Trainer in the continued exploration of my passion for fitness. I’m filled with ideas and I’m letting myself explore them. In short, I’m doing what Joseph Campbell would call “following your bliss”. I don’t know where all of this is leading to, and that’s okay. Sometimes in life you have to let yourself be lost in order to find yourself. I only have one guiding principle at the moment, and as embarrassing as it is to admit, it comes from Thor in Avengers: Endgame.

It’s time for me to be who I am rather than who I’m supposed to be.

I love you dad. I’ll see you soon…but not too soon.